A very blurred image of the partial stage of the eclipse.

A very blurred image of the partial stage of the eclipse.

Orwell Astronomical Society (Ipswich)

Solar Total Eclipse, 20 March 2015

LUCK WAS ON OUR SIDE!

Mandy and I set sail from Southampton on the P & O ship MV Oriana on Tuesday 17 March on a two week cruise to observe the total eclipse at the Faroe Islands, then onwards to Tromsø and Alta in Norway to observe the Aurora Borealis.

Things didn't start well as Oriana arrived in Southampton over four hours late due to engine problems. We eventually set sail at 8.20pm and the Captain decided that, to save time, we would take an alternative route via Lands End and the Irish Sea to reach the Faroe Islands. We made steady progress at over 20 knots hoping that the engines would behave themselves. We named our cabin "The Propeller Suite" in honour of the vibrations reaching it through the decks.

Thankfully, we made it to the Faroe Islands by eclipse day. We were approaching the harbour at Tórshavn, the Islands' capital, when I went out on deck at 07:00 UT to be greeted by overcast skies, heavy rain and strong winds. I trudged despondently back to my cabin to hear the Captain announce that, due to the wind gusting at over 30 knots, it would be unsafe to dock in the tight confines of the harbour and we would instead head out to sea in the hope of finding better weather. This sounded promising, as the Captain had weather radar on the bridge and the Tórshavn harbour Pilot was still aboard with his knowledge of local weather conditions.

We returned to the deck in a spirit of optimism at 08:00 UT to find that it was still raining but, somehow, the Sun was peeking through the clouds. These conditions continued until first contact at 08:38 UT. For the next twenty minutes we had reasonable views of the partial eclipse through our solar viewers. From 09:00 UT the skies became more overcast and the rain became heavier. Things were not looking good, but at least we had managed to observe something!

By 09:30 UT, the rain had eased and the clouds were, miraculously, starting to thin and we again glimpsed the thinning crescent Sun. At 09:36 UT, five minutes before totality, the light level began to drop and we offered up prayers for the clouds to stay away. By this time, we were approximately 10 km off the east coast of the Islands.

Totality arrived at 09:41 UT with a dramatic drop in light levels. Mandy observed Bailey's Beads and the Diamond Ring as I was busy clicking my camera. We clearly observed a red ring of the chromosphere and some fantastic naked eye prominences as the corona came into view. After thirty seconds I put my camera down to enjoy the view. At 09:43 UT totality was brought to an end by an incredible second Diamond Ring. The sky quickly brightened and we continued to observe for a few more minutes.

By 12:00 UT the winds had subsided and it was deemed safe enough for Oriana to dock at Tórshavn. We went ashore and discovered that the eclipse had not been seen on the Islands and that a Meridian Television film crew, which was meant to have joined us at Tórshavn, had also missed out. We had been incredibly lucky that the Captain had found a gap in the clouds for us. (He earned extra brownie points for enabling us to view the eclipse but subsequently lost them as the ship hit the quayside at Southampton on our return in high winds!)

My attempts at photographing the eclipse were spoilt by camera shake (per the example below). But that didn't matter, we bought some great photos from the ships photographer.

I was journeying north up the M1 (with telescope just in case) and finally hit sunshine just south of Leicester. The images in the montage below were taken in the car park of the M1 Leicester North Services. I missed first contact - the first picture below was taken just before 9.00am - but observed the remainder of the eclipse through to fourth contact.

At Leicester, the maximum magnitude of the eclipse was 87%, first contact was at 08:27:57 UT and fourth contact was at 10:41:21 UT.

My equipment was an 80 mm refractor with a glass solar filter and a very old Canon EOS300 camera. I created the mosaic in Photoshop.

The circumstances of the eclipse of 20 March 2015 meant that it was unique:

In the UK, the eclipse was much hyped, and both the BBC’s Star Gazing Live and National Science Week were re-scheduled to include it. The magnitude of the eclipse varied across the UK from 82% in the Channel Islands to almost 97% in Shetland. Totality was visible from only a relatively small tract of land in the far north (inhabited by polar bears!) In fact, there were essentially three options for observing totality: the Faroe Islands on land or at sea, or the Norwegian Arctic island of Svalbard. The weather forecast was marginally better for Svalbard, promising a greater than 50% chance of clear skies, so I decided to travel to Longyearbyen, capital of the island, and duly booked my place four years in advance of the event, as accommodation was expected to be in great demand.

I anticipated that cold weather might be a problem, bearing in mind the high latitude – the weather forecast two weeks prior to the eclipse was for a temperature of -18°C. So the order of the day was warm clothing, in multiple layers: thermals and long Johns and wind cheaters and jumpers and hats and gloves and fleeces... From the amount of luggage, one would be forgiven for thinking that the trip was for considerably longer than five days!

The journey to Svalbard was uneventful. It began with a flight from the new Heathrow Terminal 2 to Oslo, followed by an overnight stay in the Radisson Blu next to the airport, where the sudden onslaught of a plane-load of astronomers overwhelmed the check-in staff. The next day, it was onward to Longyearbyen, where we found the airport small yet functional, with friendly staff; a characteristic that matched the population of the island in general. The weather was dreary and overcast.

At Longyearbyen, our party was split between the Svalbard Hotel and the Svalbard Lodge guest house, with breakfasts taken in the Svalbar [sic], a short walk (in the cold!) from the hotel. The breakfasts were excellent, including make-your-own waffles with brown cheese and, of course, Mills Kaviar. Evening meals were expensive (well, we were in Norway and on a remote island) but very tasty, almost cordon bleu. John Mason gave eclipse talks and briefings in the local hall, the Huset. (We also ate in the Huset – but only once, due to the huge expense of doing so!) It was here that we were reminded of the possible close proximity of polar bears. Armed guards would be present throughout the eclipse, as the bears were more likely to be interested in hunting than looking at the Sun!

The weather improved after our arrival at Longyearbyen. The day after we arrived was partly cloudy, partly sunny. The day after that, the day of the eclipse, was totally free of cloud – blue sky all the way, all day. The island was heaving with visitors hoping to see the eclipse. All the big names were there. Those who couldn’t get accommodation flew in and out on the same day.

There were about 50 in our party to observe the eclipse. We were bussed to a location some 10 km out of town, along the glacial Adventdalen valley. The plan was to observe from beside the original Aurora Observatory (operational 1978-2007) but, for reasons unknown, we were moved about a kilometre further down the valley to a site at coordinates 78° 11’ 59.52” N, 15° 50’ 10.55” E. The site was empty except for a tent big enough to hold about 20 people, which also housed tables and fur-lined chairs and a fire, monopolised by our young armed guards busily chatting up each other. They passed their (loaded!) rifles around for us to pose for pictures. Refreshments were provided: hot tea and coffee and, for each of us after the eclipse, Ribena and a baguette, the latter unfortunately frozen solid when the time came to eat it!

As we were at high latitude, the eclipse occurred at low altitude (in fact, Svalbard had only just emerged from permanent winter darkness). The mountains surrounding the valley were low enough to allow the whole eclipse (1st contact to 4th contact) to be seen, and provided a dramatic backdrop. The valley itself was completely covered in snow and ice, providing a wonderful setting to view the shadow of the eclipse and the progression of shadow bands.

I set up my kit. I intended to use computer control to drive my new DSLR camera and also planned to record the temperature each minute from before 1st contact until after 4th contact. Unfortunately, the temperature during totality reached as low as -24.4°C and I hadn’t reckoned with the effect on the batteries of such extreme cold. I had taken the precaution of keeping the camera batteries warm in my pocket until five minutes before totality, and assumed that the heat produced by the laptop would be enough to keep its battery going. This might have worked at the forecast -18°C, but did not at -24°C. So, the camera worked OK, but the computer shut down about 10 minutes before totality. Unfortunately, I noticed that the computer had shut down with only one minute until totality, precipitating a panic, and I totally forgot Rule #1 of observing eclipses: if anything goes wrong with the equipment, forget it and watch the eclipse! I had received emails the day before from primary schools in Suffolk and from Lesley Dolphin of BBC Radio Suffolk asking for pictures of the eclipse and I didn’t want to disappoint them. So, as totality started, I was trying to disconnect the camera from the computer and switch it to an automatic setting (it was on manual for computer operation) – not an easy task with fingers numb from the cold, and in such darkness that I couldn’t see the controls! I tried pressing the button to take some pictures..., any pictures..., but in the end gave up and watched the eclipse. Eventually, I succeeded in bringing the camera under control and managed to catch the last 26 seconds of totality (which lasted in total for 2m 26s). I forgot to look for any other phenomena. Unforgivable! More by luck than judgement some photos did come out.

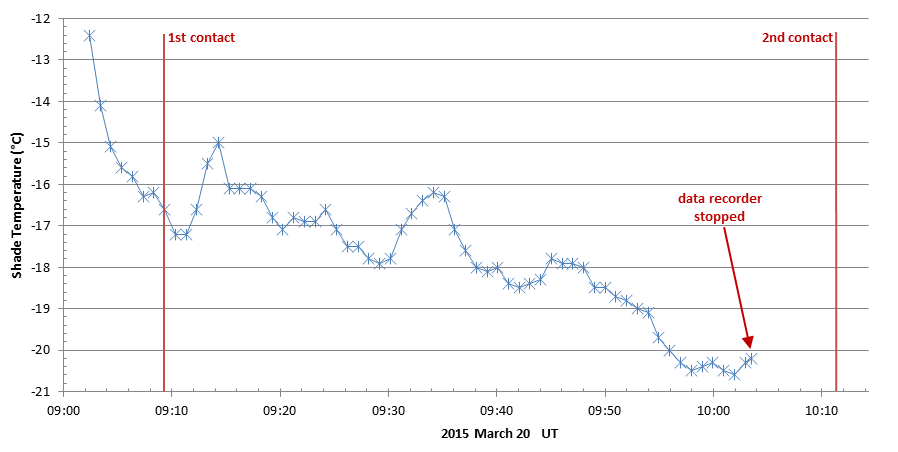

So what did I see? The shadow bands were excellent, the best I’ve seen. They started a good three minutes before totality rather than the usual 30 seconds, and really showed up on the white backdrop of the valley. There was a wonderful naked-eye red prominence visible on the upper left of the solar disk during totality. There was no aurora visible, so I didn’t miss anything there. Venus was visible easily, but I didn’t see Mars or Mercury, which in theory could have been glimpsed. The following graph shows the temperature measurements up to the point when the laptop battery died.

Temperature graph.

Temperature graph.

And what of the eclipse chasers on the Faroe Islands? Unfortunately those on land saw only rain and cloud. Some seaborne observers aboard cruise liners fared better. The P&O Oriana and the Saga Sapphire managed to sail under gaps in the clouds and their passengers saw the eclipse. Others did not fare so well.

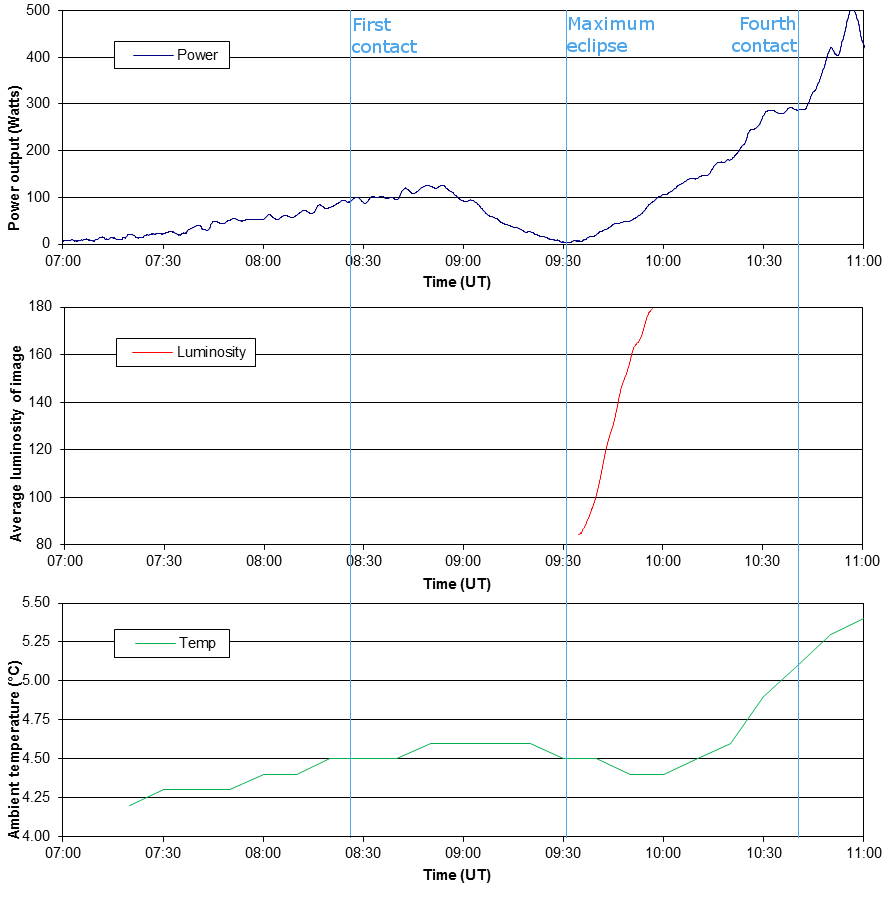

At Ipswich, 1st contact occurred at approximately 08:25 UT, maximum eclipse (85%) at 09:31 UT and 4th contact at 10:41 UT. Alan and Martin used three approaches to measure the variation in the intensity of solar luminosity during the eclipse. The results are shown in graphical form below.

Alan used a photo-voltaic solar panel array located just north of Ipswich to monitor the ambient light level. Under typical conditions, with a uniformly illuminated sky, the power produced by the array would gradually increase from dawn until around 11:30 UT (the array is oriented slightly east of south so the power doesn’t peak at midday). During the eclipse, the power increased from approximately one hour after sunrise (at 05:59 UT) until around 08:54 UT when it slowly dropped off, reaching a minimum at about 09:33 UT, then increased steadily, regaining its "normal" value by about 10:43 UT. Although the variation could have been caused by changes in cloud cover, visual observation suggested that the latter was fairly uniform throughout the period in question.

On the east side of Ipswich, Martin used a camera in a fixed position to record an image of his garden every 10 seconds from 09:35 UT to 09:57 UT (i.e. slightly over 20 minutes starting shortly after maximum eclipse). Analysis of the images using the GIMP Histogram function provided the mean image (per pixel) luminosity, showing a steady increase over the period in question. (The scale of luminosity runs from 0 for pure black to 255 for pure white.) Amusingly, the data are slightly corrupted near the start of the sequence of images thanks to a black dog running through the field of view!

Meanwhile, Martin's weather station recorded the ambient temperature in the shade. This shows a clear dip around quarter of an hour after greatest eclipse, although the change is not as marked as for power of the solar array. This confirms the impression of observers at Ipswich waterfront that the temperature dropped around this time.

The three measures are shown below, with time axes aligned.

Measures of solar intensity.

Measures of solar intensity.

From Ipswich, the event was visible as a partial eclipse, with a maximum magnitude of 87%. OASI and Isaacs jointly hosted a public observing event on Ipswich Waterfront. Unfortunately, the sky remained overcast throughout the event, so no observations were possible. Nevertheless, many members of the public attended and the Waterfront was crowded throughout.

See Fred Espenak's eclipse web site eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse.html.